The island of Mafia, lying nearby Madagascar, is the most important of a small archipelago of natural wonders which, year after year, attracts more and more sea-lovers, eager to explore the seabed of the spectacular Rufiji Marine Reserve.

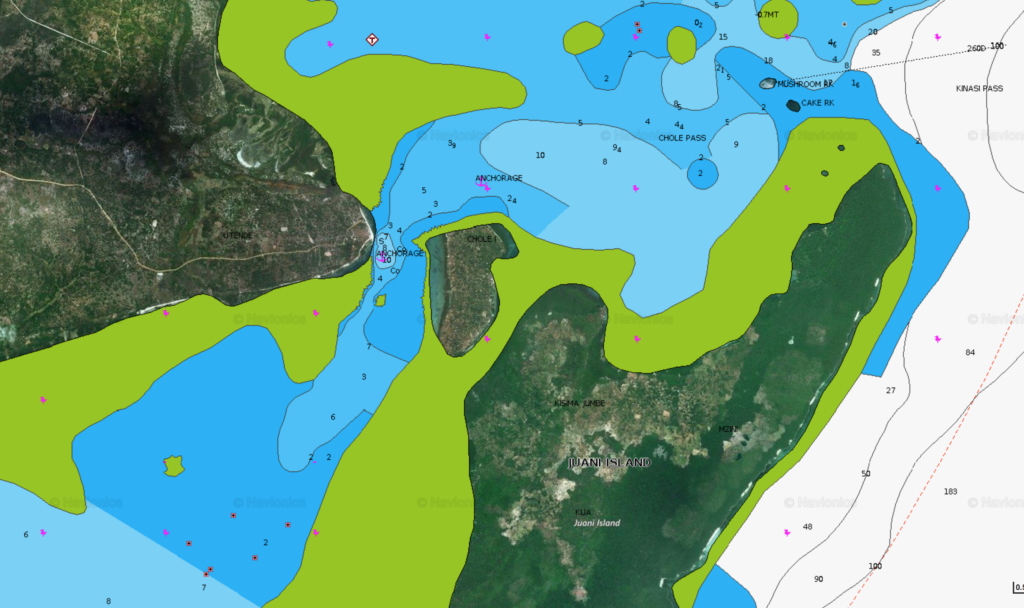

There I got acquainted with whale sharks and now I’m assuredly aiming for something wilder and more ancestral to be found in one of the lesser islands: Juani, on the southeastern side.

Juani is an island of fishermen who still live like centuries ago and cut through the sea with their palm wood trimarans. The island is famous for its cenotes, inner saltwater lakes where there are cavities probably communicating with the open sea.

“What inhabits these cenotes? That’s what I want to find out!“

To reach Juani and the largest cenotes, I definitely need to make use of a guide because we are certainly off the beaten track.

We set off by boat with the low tide rapidly advancing. Here the phenomenon of tides is rather apparent and if we do not cross the Chole Bay fast, we risk running the craft aground before mooring at Juani.

Once we reach the shore, the guide shows us the way to the fishermen’s village and here I see a reality impossible to imagine when you are in the hotel.

They have nothing but wood, mud and stone (actually coral) huts, there is no hospital, there is no lighting, there are no roads, but gravel and mud trails; there are no infrastructures. They are the only human beings on the island and being here with them transcends time. I forget for a moment about the frantic life in my town and my reality of “modern man”.

I respond to the smiles and the curious stares.

The guide introduces us to the so-called “mayor” of the village, who invites me to the town hall (actually just another hut) to sign a visitor’s book, written in their own language and which I obviously blindly sign out of politeness. Everything captivates me and distracts me from the real reason for my visit. I am charmed by their hospitality and their kindness. However, women are an exception; they remain on the side and almost disappear whilst we are walking through the village.

After fulfilling our obligations, my guide and another fisherman from the village lead me to the cenote, through a trail leading from the village to the forest. Along the way I have the guide translate the questions my curiosity inevitably brings about. The first is about health and the fisherman answers that it is the biggest problem because, even for a simple toothache it is necessary to go to the capital, where there are doctors and a hospital, or seriously risk death.

Our walk lasts about twenty minutes of a stony path, trees, bushes baobabs and heat! The temperature is high and the air dry. The forest protects me from the sun but my only wish is to reach the cenote to get in the water.

We encounter the first two cenotes and I would like to start my exploration: I am impatient, but they want to take me to the largest, the deepest one.

Well, the desire to discover this seabed and what lives in it is stronger than any fear and discomfort. But the wait is over.

Exploration begins. Diving in saltwater in the middle of the forest is a strange feeling. I dunk my face inside right away, to see what is below. I am just too curious.

trip to Mafia Island

The first things I see are plants and sponges never seen before, not even in the very same ocean a few hundred meters from here. The habitat here must be “independent” from the sea, even if the saltwater leads me to believe that there is a sort of communication with the ocean, and this is supported by the fact that the cenote undergoes a tidal regime.

I cross the lake and I find a first cavity, whose bottom is invisible, even with a flashlight; near the entrance I find a species of fish never seen before and not corresponding to any of those observed on the nearby reef.

trip to Mafia Island

They are elusive and, as soon as I approach, those fish dip down in the dark cavity. After exploring this side of the lake, I return to my access point, still looking for other forms of life: I find another cavity even larger and deeper.

I try to partly slip in and illuminate it, but it is dark here. I see other decent-sized fish, shy and unseen. Incredible, who knows what species they are and if they have been photographed and classified. I would like to have more breath to penetrate the darkness to see what else is hidden there and maybe even discover the connection with the open sea. But wisely I settle for what I have seen.

By now, a few hours have gone by and I have explored the center and the edges of the cenote, so I make for the exit, also not to keep my companions waiting for too long.

We return to the landing where we left the boat, and by now the tide is at its minimum and uncovers a long strip of coast of this bay: another spectacular sight and still all the time ion the world to admire it.